Chapter 1: Subūra

Sabīna: read the story (p. 7)

tū dormīs?

hōra prīma est.

ego sum in popīnā.

ego semper labōrō!

ubi es tū?

ego sum in īnsulā.

Sabīna?

ego nōn legō!

tū es mendāx!

The Subura (p. 12)

Sabina and her family are living in the Subura, a densely populated district near the centre of Rome, in AD 64. Here huge numbers of people lived packed together in multistorey apartment buildings, and the population density was probably greater than that of modern London or New York. As well as being a residential area, the Subura was a centre of trade and manufacturing. Its narrow, crooked streets were notorious for noise, bustle, and dirt.

At night the streets were unlit, and violence and crime were common. Many of the streets had no pavements and were too narrow for traffic. In order to reduce congestion in the wider streets, wheeled traffic (with the exception of carts carrying building material) was banned in the city for most of the daylight hours.

tū errās clāmōsā in Subūrā.

You wander about in the rowdy Subura.

The poet Martial wrote this to his friend. Martial came from Spain to live in Rome in AD 64.

Juvenal was a poet living in Rome in the late first century AD. In his poems he attacks the vices of Roman society and complains of the difficulties of living in Rome. Here he describes the risks of walking around the city at night:

Now think about the dangers at night:

what a great distance it is for a tile to fall

from the top of the roof and hit you on the head;

how often a broken pot drops from a window;

how hard it hits the pavement,

chipping and cracking the stones.

If you go out to dinner without making your will,

people might think you are lazy,

that you don’t take into account the possibility

of sudden disaster. There are just as many

chances of dying as there are open windows

above you as you walk past at night.

And so, you should hope and pray, as you pass by,

that the tenants are satisfied

with emptying out their full chamberpots.

QUESTIONS

- According to Juvenal in this passage, why was it dangerous to walk around Rome at night?

- How reliable do you think Juvenal’s description is?

Few blocks of flats from ancient times survive in Rome. This image shows a road in Ostia, the harbour town near Rome.

A busy street in modern day Naples, above, and a street with apartment buildings from ancient Ostia, below. How similar do you think a street in the Subura might have been to these two?

Language note 1: who's doing what? (p. 14)

-

Look at these sentences:

ego semper labōrō. ego in Subūrā habitō. tū in īnsulā labōrās? tū in popīnā dormīs. amita in popīnā labōrat. Sabīna in īnsulā legit. -

In Latin, the ending of the verb tells us who is carrying out the action.

-ō e.g. ego labōrō I work, I am working -s e.g. tū dormīs you sleep, you are sleeping -t e.g. pater intrat the father enters, the father is entering -

The verb in the following sentences follows a slightly different pattern:

ego sum Sabīna. I am Sabina. tū es mendāx. You are a liar. Subūra est clāmōsa. The Subura is rowdy. -

Note that est can mean is, it is, or there is:

hōra prīma est. It is the first hour. popīna estin Subūrā. There is a bar in the Subura.

Language practice 1 (p. 14)

-

Translate these sentences:

a. ego in īnsulā habitō. d. ego in cellā legō. b. tū in popīnā labōrās. e. tū nōn dormīs. c. Sabīna intrat. f. ego labōrō. -

Translate these sentences:

a. ego sum in īnsulā. b. negōtiātor in Subūrā est. c. tū es in popīnā. d. Subūra nōn est quiēta.

This image shows a 30 m high firewall built from nearly indestructible volcanic rock. The wall separated the Forum of Augustus, of which the remains can be seen in the foreground, from the Subura. The wall ensured fires couldn’t spread to the Forum from the apartment blocks of the Subura, and also created a physical barrier between the grand, marble Forum and the cramped and dirty Subura behind it.

The population of the city of Rome (p. 15)

Come, look at this mass of people, for whom the roofs of the vast city of Rome can barely provide shelter. The majority of them are away from their homeland. They have flocked here from their rural towns and cities, from all over the world. Some were brought here by ambition, others by the need to run for office, or as an ambassador, or to enjoy the luxuries of city life, a good education, or the public games. Others have come because of a friendship, or on business, for which there are great opportunities here. If you ask them all, ‘Where are you from?’, you’ll find that the majority of them have left their homes to come to this greatest and most beautiful city, though it wasn’t their home city.

Seneca, Letter to his mother Helvia.

In AD 64 about one million people lived in the city of Rome, making it the largest city in the western world until London in 1801. All these people lived in a relatively small city. The fact that a large part of the city was taken up by temples, palaces, fora, theatres, circuses, and the great town residences of the rich and powerful, meant that the majority of the population lived in densely populated areas. Probably the most famous of these neighbourhoods was the Subura.

Coming to Rome

Rome attracted people both from nearby regions in Italy and from the farthest reaches of the Empire. Wealthy people might have come to Rome to undertake a career in politics, ordinary people might have been attracted by the employment opportunities in the large city, and the very poor might have arrived in the hope of receiving the free grain dole that the emperor gave out. The largest group by far, however, were enslaved people. They came to Rome against their will and most of them were then sold at the many slave markets in the city.

A multicultural city?

It is hard to work out what percentage of Rome’s population had migrated to the city, rather than being born there. Estimates of the total number of immigrants vary from 6% to 30%, so possibly as much as a third of the city’s inhabitants were not from Rome originally. And a much larger percentage of the population would have had parents or grandparents who weren’t from Rome.

Although many people moved to Rome from elsewhere, it is hard to know how multicultural the city would have felt to a modern observer. A wide variety of cultural and religious practices from across the Empire flourished among the immigrants living in the city, and Romans of all backgrounds embraced their new traditions and religions. Judging from the records that survive, it seems that people did not often state where they came from. This suggests, perhaps, that it was not considered particularly important to them. The extent to which immigrants and their descendants felt like outsiders, or slotted seamlessly into a multicultural melting pot of peoples, is nearly impossible to know.

QUESTIONS

- What opinion do you think Seneca has of the newcomers to the city?

- Compare the makeup and density of Rome’s population to that of your own town.

Seneca, a well-known Roman intellectual, was tutor and adviser to the young Emperor Nero during the early part of his reign.

Lūcīlius: read the story (p. 16)

Lūcīlius

hōra octāva est. Subūra nōn est quiēta. Subūra est clāmōsa.

Faustus est in īnsulā. fīlia est in popīnā. Sabīna in popīnā labōrat.

servus est in viā. servus prō lectīcā ambulat. iuvenis est in lectīcā.

iuvenis est Lūcīlius. mendīcus est in viā. mendīcus est Mānius.

5Mānius salvē! ego sum mendīcus!

servus tū nōbīs obstās!

Sabīna ē popīnā exit.

Sabīna Mānius est senex!

Lūcīlius ē lectīcā exit. hercle! tēgula cadit.

10Sabīna cavē!

tēgula in viā cadit. Lūcīlius est perterritus.

Sabīna Subūra est perīculōsa! certē tū in Subūrā nōn habitās.

Lūcīlius ērubēscit. Sabīna rīdet. Mānius nōn rīdet.

Replica Roman roof tiles.

Women at work (p. 17)

Some women, like Rufina, worked outside the home. It is difficult to know how many women did work, and how much of the work in Rome was done by women (whether enslaved or free). This is because there is relatively little evidence for women working. This may just be because of a bias in the way Romans represented working women, though it might also suggest that it was less common for a woman to have a job.

The lack of evidence might be explained by the fact that many women must have been occupied with having and raising children and domestic work, such as making clothes. Many probably helped in their family business, but this could go unrecorded in our evidence. However, we do also know about women in specialist occupations, such as textile- workers, doctors, and artisans, as well as about women doing jobs usually associated with men (fish sellers, innkeepers, barbers). Additionally, there were women working as performers, dancers, and sex workers.

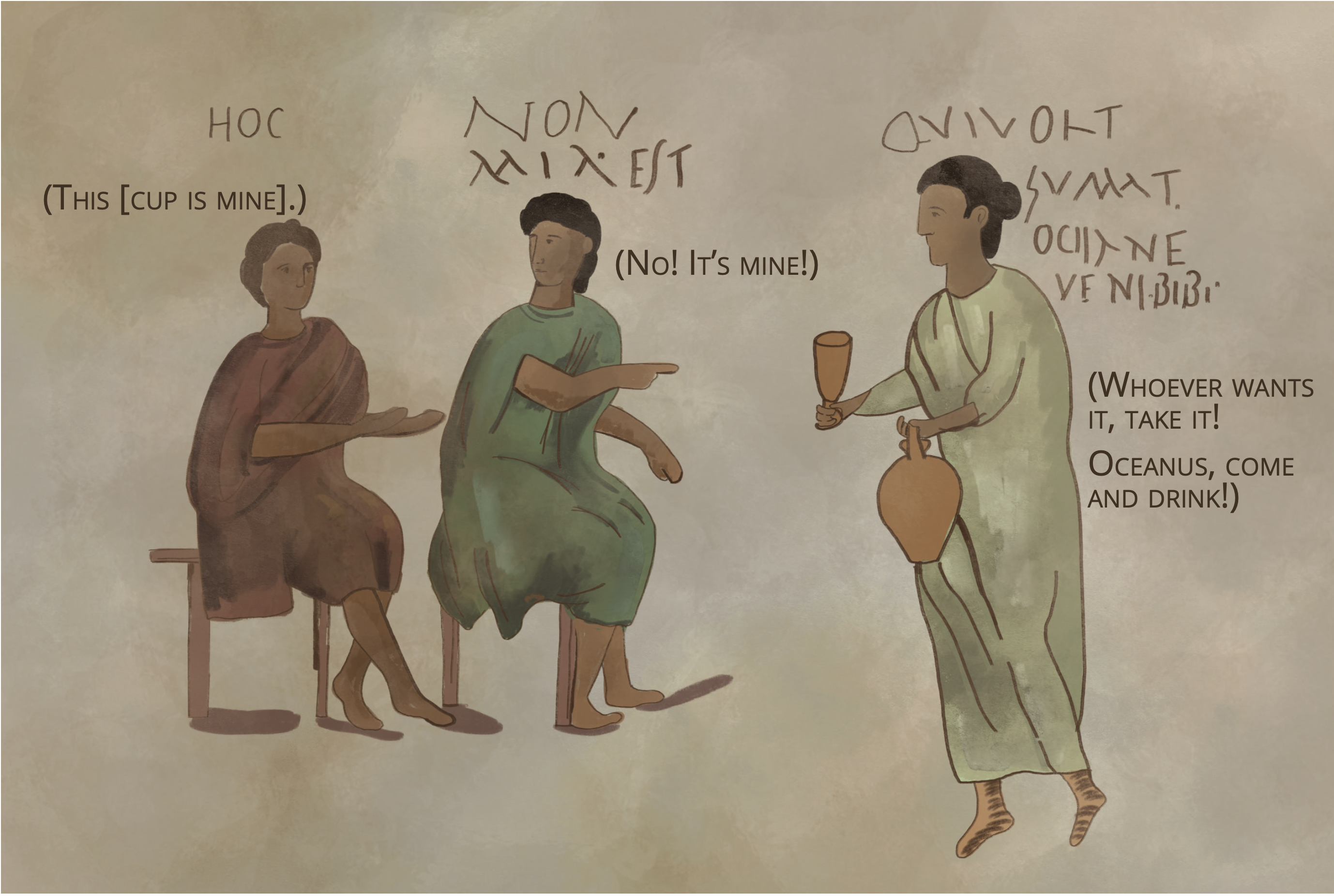

Drawing of a wall painting from a popīna in Pompeii, in Italy.

QUESTION

Living in an insula (p. 18)

The Latin word for a block of flats is īnsula, which literally means ‘island’. The apartment blocks probably got this name because the separate buildings surrounded on all sides by streets resembled islands surrounded by sea.

Like the vast majority of Rome’s population, Sabina’s family lived in a rented flat in a multistorey block. Only the very wealthy owned their own house. Sabina’s father was the landlord of an insula. Faustus didn’t own the building; the owner would be a rich man who had bought the insula as an investment. The landlord was responsible for managing the property and collecting rent from the other tenants. Rents in Rome were extremely high, so evictions for non- payment must have been commonplace.

High rent wasn’t the only problem tenants faced. Many of the blocks were flimsily built, with foundations which were not strong enough to support the structure. As a result, these ramshackle buildings often collapsed or caught fire.

Rich and poor lived in the same building. Unlike modern high-rise blocks where the penthouse is often the most desirable apartment, in a Roman insula the best accommodation was on the ground and first floors, while the poorest tenants had rooms on the upper floors and in the attics. The risks from fire and collapse were greater on the upper floors. Moreover, there was no running water on the upper floors, so the tenants at the top had to collect water from the public fountains and carry it up several flights of stairs. The rooms at the top were dark and, in winter, they could have been very cold. The windows did not have glass, so the only protection from the wind and rain was wooden shutters or curtains. Some tenants owned a portable heater (foculus), which would have heated the room by burning wood or charcoal, creating a very smoky atmosphere.

The ground floor of an insula was often divided into shops and workshops, which had openings facing onto the street. These units sometimes had a backroom or a mezzanine floor where the shopkeeper or craftsman and his family lived – very cramped quarters for a family. (A mezzanine is a half-floor, between the ground floor and the first storey, which was accessed by a ladder.) There were all kinds of shops and workshops in the Subura – bakers, barbers, cobblers, and many others – and lots of places selling food and drink either to eat in or to take away. Many flats had very limited cooking facilities, perhaps an open fire, or none at all, so if people wanted cooked food they had to eat out. Many people would have survived on a diet of bread, cheese, and fruit.

For most of its inhabitants, life in Rome was dangerous, unpredictable, and, compared with what we are used to, unsanitary. As accommodation was so cramped and cooking facilities limited, most people would have spent a lot of time outside, so public spaces and amenities were very important.

oil lamp

chamber pot

fountain

oil lamp

chamber pot

fountain

Inside of the remains of an insula in Rome, built just a short distance from the temples of the Capitoline Hill.

Language note 2: reading Latin (p. 20)

-

Look at these sentences:

ego in Subūrā habitō.

I live in the Subura.Sabīna in popīnā labōrat.

Sabina is working in the bar.The Latin sentences tell us who is carrying out the action, then where, then what they’re doing. The English sentences tell us who is carrying out the action, then what they’re doing, then where.

-

Look at these sentences:

Sabīna est in cellā.

Sabina is in the room.ego sum in Subūrā.

I am in the Subura.In these Latin sentences, the order of the words in the Latin and the English is the same.

-

When you are reading Latin, try to read it from left to right and get used to the order in which the information comes.

-

If you are translating into English from Latin, you will need to make your English sound natural.

Language practice 2 (p. 20)

-

Complete the sentences with a correct choice, then translate your sentences.

ego tū ambulat habitō iuvenis dormīs a. .... in lectīcā dormit. d. .... nōn sum in cellā. b. .... labōrās, soror? e. .... Sabīna in viā c. ego in Subūrā .... . c. tū in īnsulā .... .

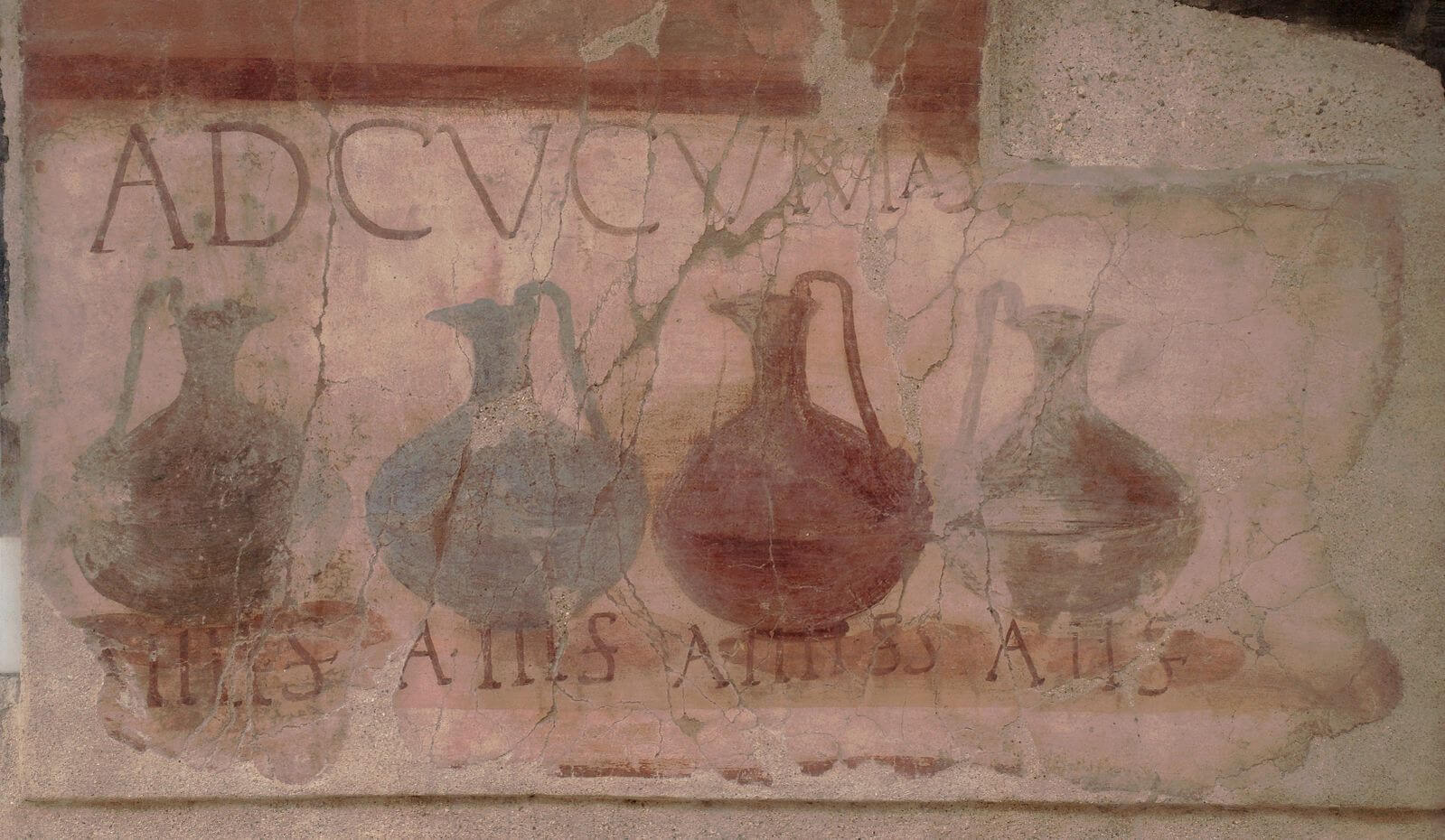

Sign advertising wines for sale at a popina in Herculaneum, in Italy. The popina is called ad cucumās (at the cooking pots). Four different wines are sold, at 4, 3, 4, and 2 assēs (pence) per sextārius (about half a litre).

nox: read the story (p. 21)

nox

nox est. Sabīna in cellā est. Subūra nōn est quiēta.

Sabīna nōn dormit.

turba in popīnā est. Rūfīna in popīnā labōrat. Faustus in popīnā bibit.

fūr quoque in popīnā est. fūr est pauper.

5Faustus Rūfīna! ubi es tū, soror?

Rūfīna quid est, frāter?

Faustus fūr est in popīnā!

Rūfīna quid? fūr est in popīnā? ubi est fūr?

Faustus tū es fūr! vīnum est nimium cārum!

10Rūfīna tū es asinus, frāter. vīnum nōn est nimium cārum.

tū nimium bibis!

Faustus ērubēscit. turba rīdet. fūr quoque rīdet. popīna est clāmōsa.

turba nōn est cauta. fūr nōn est pauper.

Above: a popina in Pompeii, with vats sunk into the bar.

Below: a wall painting from Pompeii, showing people playing dice in a popina.

Sabina’s aunt runs a popina, a bar which sold drinks and food for people to take away, eat on the street, or consume inside. Romans drank wine, which they mixed with water. In a popina the wine was stored in jars (amphorae), and then transferred to jugs for serving. Hot food was cooked on a stove and probably served from the pan.

Rome in AD 64 (p. 22)

Beginnings

The origins of Rome are shrouded in mystery. The original settlement expanded from a secure hilltop location, gradually absorbing its neighbours until it dominated the whole Italian peninsula.

The descendants of those early settlers wanted to create a date for the foundation of their city. Using calculations based on the four-year cycle of the ancient Olympic Games, the Romans chose the year 753 BC for the beginning of Rome. They even selected a date: to this day modern Romans celebrate their city’s birthday on 21 April. By the time Emperor Augustus established one-man rule in 27 BC, more than 700 years later, Rome was the centre of a vast empire (see the map on pages 2–3).

Nero

In AD 54 the teenage Nero became the fifth emperor. The title of emperor always passed down through the male line, because women could not hold political office in Rome. However, some female members of the imperial household, including Nero’s mother Agrippina, exercised considerable power.

By the time our story begins, Nero has been emperor for ten years. The early part of his reign was relatively stable. The young emperor was under Agrippina’s control and supervised by two advisers: the philosopher and intellectual Seneca (see page 15) and a military commander called Burrus. Violent uprisings at opposite ends of the Empire were successfully put down, and in Rome Nero behaved as a generous and benevolent ruler.

Nero was also a great supporter of the arts. Unusually for an emperor, he took part in plays himself, and he gave poetry and musical performances. He was also a fan of sports, and on occasion drove chariots in races (where his competitors let him win).

However, there was another side to Nero’s character, and he did not cope well with the power available to an emperor. His behaviour became more erratic and cruel, and on his orders increasing numbers of people (usually those who displeased him or he felt were a threat) were exiled or killed. Just five years into his reign, he even had his mother killed, possibly because she disapproved of an affair he was having, or because he resented her attempts to control him. Perhaps it was a combination of the two. From that point on, he set few boundaries on his own behaviour.

Nevertheless, Nero’s support for arts and sports made him popular with much of the population of the Empire, particularly the poor, who benefited most from the spending on entertainment. Others felt that it was not appropriate for an emperor to act in plays or take part in chariot races. Some wealthier Romans resented his legal and tax reforms which benefited the common people.

Most of our information about Nero comes from Roman historians, who themselves belonged to the wealthy upper classes and were hostile to Nero. However, like us, Romans were a broad mix of people, with a range of views and interests. In AD 64 different individuals would have had varying opinions about their city and their emperor.

Gold coin with the head of Nero, from AD 66. It is printed with the words IMP NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS. IMP is an abbreviation of imperātor, which means ‘emperor’.

The abbreviation AD stands for Annō Dominī (meaning ‘in the year of our Lord’). We use it to indicate a year after the traditional date of the birth of Jesus Christ. A year BC is ‘before Christ’. AD is not the only Latin abbreviation that we still use in English. Can you think of any others?

Traditional foundation of the city of Rome.

Augustus becomes sole ruler of the Roman Empire.

Nero becomes emperor at the age of 16.

The year our story begins. How old is Rome?